Wise Altruism: Doing Good under Radical Uncertainty

Questions about how to do the most good, or best to ‘contribute to the world’, are beset with massive uncertainties. Different models of the nature of this uncertainty suggest different practical approaches. Recent work in the cognitive science of rationality offers insight when dealing with especially radical forms of uncertainty. This has implications for how we should understand the project of Effective Altruism.

The Big Question

This might ring a bell: you want to ‘contribute’ to society or ‘make the world a better place’ but you’re really unsure about how best to do that.

It’s not that everything is uncertain: for example, you might be confident that the world would be better if someone other than Trump were the president, or if countries could coordinate better on achieving our climate goals.

But you’re still deeply uncertain about what, specifically, you, specifically, should do about these issues - and indeed whether other issues, such as helping avoid nuclear war, or addressing risks from AI, should be your focus instead.

Decision Theory to the Rescue?

In economics, philosophy, and statistics, decision theory has long been the go-to framework for making decisions under uncertainty - including the kind of practical uncertainties just mentioned.

The foundational ‘expected utility’ model formalised by John von Neumann and Oskar Morgenstern instructs us to weigh the benefits of each possible outcome by its probability and choose the action with the highest expected value.

It’s a powerful approach if you know what your goals are. Suppose you’re choosing which charity to donate to, and your goal is to save lives that would otherwise be lost to Malaria.

You crunch the numbers and find that one charity has a 50% chance of saving 10 lives for each dollar donated, while another has a 40% chance of saving 30. Calculating the expected values in each case (5 lives vs 12 lives respectively) then gives you a clear basis for your choice.

And you might try to apply this same approach to questions around your choice of career. You could try to quantify how many lives you save per year of being a doctor, for instance, and compare that to the option of becoming a wealthy entrepreneur and donating a significant amount each year to the previously identified charities. If you also think that your skills and experience give you a good chance at achieving this goal, you might conclude on this basis that you can do the most good by ‘earning to give’: becoming rich and donating your wealth.

This decision-theoretic approach to the practical question of how to do the most good in the world has been successfully promoted, in recent decades, by the ‘effective altruism’ (EA) community. Influential EA organisations like GiveWell and 80,000 Hours produce detailed research of this sort on which charities “save or improve lives the most per dollar” and which careers most effectively tackle the world’s biggest problems.

But, as we’ll see, there are often reasons why a simple decision-theoretic approach of this sort just won’t work.

Effective Altruism and Deep Uncertainty

The EA movement is sometimes criticised for placing too much emphasis on metrics and data. But, perhaps surprisingly, the causes often recommended by EA in more recent years have been rather speculative in nature, such as reducing ‘existential risks’ (those that threaten our long-term future) from, say, AI and engineered pandemics.

This is in part because of the work of people like Toby Ord - one of the founders of the EA movement - whose book The Precipice (2020) tries to extend the methods of quantitative rationality to these more nebulous areas.

Ord argues, for instance, that we can rationally assign a 10% chance that all intelligence life on earth is eliminated due to advanced AI - and that since the number of future generations of potentially happy lives that would thereby be lost is staggeringly large, the ‘expected value’ of working to reduce this risk is extremely high - so this kind of work is an obvious choice if you’re seeking to make the world better.

But this application of decision theory to more speculative, big picture issues (sometimes associated with the ‘Second Wave’ of EA) raises thorny questions about the scope of this quantitative approach.

Moral Uncertainty

For example the question of the value and number of future generations that should be taken into account in the moral calculus depends critically on controversial philosophical views around moral consequentialism and population ethics.

But the massive uncertainties around these views themselves are not taken into account when crunching the numbers in the way just described.

This issue is addressed directly in Moral Uncertainty (another book published in 2020), by Toby Ord (again), William MacAskill (perhaps the main thought-leader of the movement) and Krister Bykvist.

They explore the question of what to do when different philosophical and ethical approaches give different conclusions - as they often in fact do. When making decisions ‘under moral uncertainty’, they conclude, we should try to aggregate - in rational and sometimes quantitative ways - the implications of different moral approaches.

You could try, for example, to see how the value of working to reduce AI risk varies on different philosophical and ethical approaches, and then weight these values by how likely it is that each of those approaches is the right one. If the impact of working on AI risk still comes out higher than working on climate change, then you still have a clear practical guide to action.

Model Uncertainty

A related kind of fundamental uncertainty that affects assessments of the likelihood of annihilation by AI or other risk outcomes, is that such estimates are typically based on a quantitative model - which may turn out to be wrong.

Even within the EA and AI risk communities, people like Eliezer Yudkoswki who assert a very high likelihood for humanity’s future annihilation by AI are sometimes criticised for failure to incorporate model uncertainty - the probability that their models of the situation are wrong - into their ‘P(doom)’ - their estimate of the probability that such annihilation occurs.

As with moral uncertainty, model uncertainty is often discussed in contexts where the recommendation is to try to quantify the very uncertainty that originally derives from applying a rational, quantitative approach.

The chance that your model is correct is itself something you try to put a figure on - an approach that is also popular in the field of climate science, where different models simulating the earth system give radically different results for the future impacts of climate change, and the most widely shared forecasts are in fact weighted aggregates of the result of these different models.

Deep Uncertainty

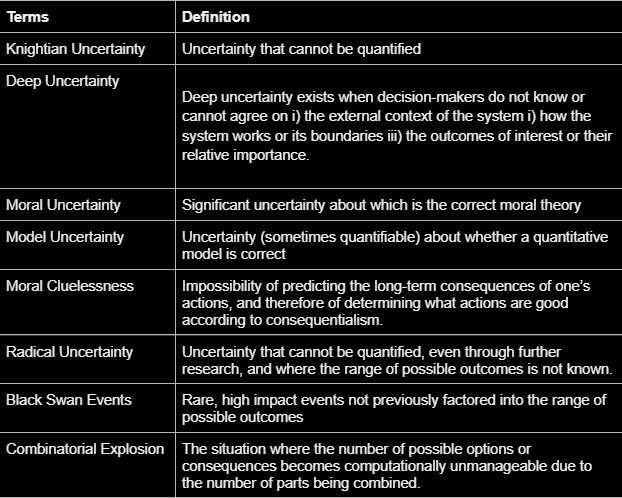

Zooming out, moral uncertainty and model uncertainty can be seen as examples of what is sometimes called ‘deep uncertainty’. This term derives from a 2003 paper on quantitative, long-term policy analysis generated by the RAND corporation, where it’s defined as a situation where decision-makers don’t know or cannot agree on i) the external context of the system ii) how the system works or its boundaries iii) the outcomes of interest or their relative importance.

Research in this tradition, including a recent volume Decision-Making under Deep Uncertainty (2019) recommends approaches such as ‘robust decision making’ - strategies that perform well across a wide range of plausible futures - and ‘dynamic adaptive policy pathways’ that can evolve over time in response to a changing environment.

From Deep to Radical Uncertainty

It may be, though, that these ‘deep’ uncertainties don’t go deep enough.

In the approaches just described, deep uncertainty is seen as a reason to introduce new tools and methods, for example attempting to quantify the level of moral and model uncertainties involved in our expected utility calculations, and attempting to specify a range of plausible futures over which strategies can be assessed.

But perhaps the world is just not the sort of place that these kinds of extension of basic decision theory can get a good grip on.

Cluelessness

Fundamental doubts of this kind are being raised even within the EA community. Hilary Greaves (Oxford Philosopher and founder of the EA-aligned Global Priorities Institute) has raised the issue under the heading of ‘cluelessness’.

The idea of cluelessness has been around for some time as part of a standard critique of consequentialism: that it’s just not possible, most of the time, to predict the long-term consequences of your actions. But Greaves considers how the idea also applies to the more applied ideas found in EA.

In a talk at the EA Student Summit in 2020, Greaves made the case that the ‘first wave’ EA approach of choosing actions based on clear metrics such as number of lives saved from malaria, simply does not take into account the longer-term or systemic consequences of such actions, which likely outweigh the short-term benefits.

And such longer-term consequences, she argues, are simply impossible to quantify - either with respect to their objective impact or likelihood, or with respect to our subjective ‘credences’ - how confident we should be in our beliefs. Moreover, we cannot assume that the range of possible good and bad long-term consequences simply cancel each other out - we are instead forced to make difficult judgements about whether those consequences will be more good than bad.

While she herself does research in the area of how to aggregate different perspectives under moral uncertainty, her conclusion - expressed for example in her interview on the 80,000 hours podcast - is that such attempts to use formal methods to quantify the higher-level uncertainty here are themselves highly uncertain, for example relying on dubious axioms, and controversial methods of comparing results across ethical theories.

She concludes:

I think we’re just in a very uncomfortable situation where what you should do in expected-value terms depends…on what feels like a pretty arbitrary, unguided choice about how you choose to settle your credences in these regions where rigorous argument doesn’t give you very much guidance.

This points us toward a more radical kind of uncertainty - one that can’t be addressed by more of the same formal or decision-theoretic approaches.

Radical Uncertainty

In their book Radical Uncertainty: Decision-Making for an Unknowable Future (2020), Mervyn King and John Kay spell out this more fundamental kind of uncertainty.

Radical uncertainty, for them, is not just the ‘Knightian uncertainty’ of being unable to quantify impact or likelihood. It is the kind of uncertainty where the situation is in principle unresolvable by further research - and where we have, in addition, the problem of not knowing what the range of options or possible futures even consists of.

The idea of ‘black swan’ events - rare events that were hard to even conceive of before they occur - has become well-known through the 2007 book of that name by Nassim Taleb, but King and Kay point out that this situation generalises: even in more everyday, less high-impact contexts, it’s often impossible to come up with a complete list of possible outcomes.

And as they also point out, one of the axioms of standard decision theory assumes that such a complete listing is possible (the so-called ‘Completeness’ axiom) - so this point provides a very clear way of understanding the limits of that approach.

Another thinker who stresses the role of previously inconceivable events is physicist and philosopher David Deutsch, who emphasises the importance in world history of scientific discoveries which, by their very nature, cannot be foreseen - since such foresight would itself require a discovery of the same sort.

A similar level of fundamental uncertainty also occurs in the theory of complex systems. Indeed complex systems are often defined as systems whose behaviour is unpredictable in principle from their individual components. Instead, complex systems exhibit emergent and sometimes chaotic behaviour where a very small cause can have massive - and unpredictable - effects.

If human civilization and its interactions with the natural environment can be thought of at least in part as a complex system, this would help explain why we experience the radical uncertainty described by King and Kay.

The Role of Narrative

How, then, can we do good in a world of radical uncertainty? In their book, Kay and King advocate for narrative reasoning and judgment.

Rather than use formal models, we can often construct plausible stories to navigate massive complexity. This approach resembles the ‘abductive reasoning’ - inference to the best explanation - often used in fields like medicine, law, and intelligence analysis.

In particular, when dealing with global affairs, world leaders need big picture ‘reference narratives’ that tell them “what’s really going on here”. Such narratives should be based on science and data where possible, but should also be lightly held, with an understanding that new data and narratives can emerge at any time.

The Great Rationality Debate

Kay and King’s answer resonates with trends in the cognitive science of rationality.

Recent work in this area builds on and responds to psychologist Daniel Kahneman’s influential dual-system theory of cognition. System 1 thinking is fast, intuitive, and emotional; System 2 thinking is slow, deliberative, and analytical.

Kahneman emphasized the biases of System 1 and the corrective power of System 2. When choosing how to do the most good, System 2 encourages us to resist impulsive empathy and instead maximize our impact with rational analysis - very much as Effective Altruism does.

However, more recent work - especially by Gerd Gigerenzer - challenges this approach, resulting in what has been called ‘The Great Rationality Debate’.

Gigerenzer argues that heuristics (the quick-and-dirty rules used by System 1) are not just cognitive shortcuts, but often the best tools for decision-making in complex, real-world environments.

In uncertain domains, a well-tuned heuristic - or narrative, we can add - outperforms a flawed rational model. This is sometimes called ecological rationality: the idea that a heuristic is rational insofar as it fits the environment in which it's used.

This raises an important question: Should we try to “correct” our intuitions with analytic thinking, or should we instead cultivate and improve the intuitions themselves?

Vervaeke and the Cultivation of Wisdom

Cognitive scientist John Vervaeke, whose Youtube series Awakening from the Meaning Crisis has allowed him to reach a wide audience, has outlined (e.g. in this recent paper co-authored with Anna Riedl) a position that integrates these two approaches to rationality under radical uncertainty.

While he recognises that there are times when we need to correct our intuitions with rational models, he also argues that we’ll often instead need to cultivate our intuitions, or in his terms our capacity for ‘relevance realization’.

Relevance realization is the agent’s ability to filter information, focus attention and identify what matters in a given context or ‘arena’ of action. This is crucial, he argues, in avoiding ‘combinatorial explosion’: the situation where the number of possible options or consequences becomes computationally unmanageable.

In chess, an expert doesn't - and couldn’t - calculate every possible move. They see what’s relevant, and plan out only a limited range of move sequences. The same is true for moral and strategic reasoning.

Vervaeke argues that wisdom involves exactly this sort of dynamic interplay between analysis and intuition, supported by practices that deepen one’s insight. These include mindfulness, dialogical inquiry, philosophical reflection, and even contemplative practices. Wisdom is thus not the opposite of rationality - it is its mature form, incorporating emotion, embodiment, and experienced meaning.

Perception of Value and Moral Circle Expansion

Vervaeke’s work is a scientific framing of closely related ideas in philosophy and ethics.

The ethical systems discussed in EA often emphasize reason, rules, and consequences. But another strand of moral philosophy - drawing from phenomenology, virtue ethics, and contemplative traditions - focuses on moral perception.

Max Scheler and Edith Stein - both early twentieth century thinkers in the ‘phenomenological’ tradition - described love and empathy as perceptual capacities that disclose the value of others. Similarly Vervaeke describes how the Christian idea of love as ‘agape’ can amount to a radical reshaping of relevance-realization.

Martin Heidegger and Maurice Merleau-Ponty saw ethical understanding as grounded in lived experience and embodied concern, and indeed are often seen as forerunners of the ‘embodied, enactive’ approach to cognitive science that Vervaeke develops.

Buddhist philosophy and practice also offer tools for expanding our moral intuitions.

Vervaeke and Riedl point out that ‘non-dual awareness’ or ‘mindful meta-awareness’ practices can help people

extend their attention beyond current aspectualizations to experience the embodied surplus of meaning, which then can lead to insights into more generalized notions that encompass more relevant aspects of reality

Another relevant practice is ‘metta’ - also known as ‘loving-kindness’ meditation - which, as Vervaeke observes, can help cultivate an existential stance involving love and compassion to friends, strangers, and humanity as a whole. Such practices offer an alternate approach - more embodied and less abstractly theoretical - to the ‘moral circle expansion’ promoted by Effective Altruists.

While EA has explored meditation practices as tools for enhancing personal effectiveness and avoiding burnout, it has tended not to appreciate the epistemic and ethical role of such practices: their ability to improve the experienced process of decision-making in real, living contexts.

Wise Altruism

We’ve seen how the ‘deep’ uncertainties around both system models and moral theories point towards a more radical uncertainty - one that shows up the limitations of decision theory and thereby the mainstream of Effective Altruism when addressing the question of how to make the world better.

The impossibility - not just in practice, but in principle - of quantifying uncertainty in many real practical cases of trying to do good, points to the need for a new approach harnessing narrative, heuristics and educated intuition.

This new approach - let’s call it ‘Wise Altruism’ - involves recognising both the value and limits of formal rationality in considering ways to do good: it’s not about simply rejecting decision-theoretic and standard EA approaches.

There will be many scenarios, such as choosing between charities once you know that you want to make an impact in a particular area, where crunching the numbers can really help with decision-making.

Even when trying to establish an overarching ‘reference narrative’, quantitative models (such as those used in complex systems science) can be helpful in clarifying one’s thoughts and providing direction - as long as we remain aware of their limitations as models. I’ve written elsewhere of the scientific grand narratives that attempt to use data and evidence in a sensitive way to point towards tentative big picture visions.

Quantitative models depend on axioms and assumptions that reflect a particular framing of the problem space. Wise Altruism looks to narrative reasoning and to meditative and contemplative practices to enable insightful reframing of the situation.

As with Effective Altruism, Wise Altruism is best seen as a general approach rather than a specific set of recommendations. Depending on the framing that ultimately make sense to them, those applying this approach might still (as advised by EA) work on AI risk, animal suffering or global poverty reduction, though perhaps with a greater appreciation of the complexities involved - or they may find deeper meaning in narratives around climate catastrophe or cosmic complexity, metacrisis or cultural evolution.

Wise Altruism is not ultimately about objectively resolving the uncertainties we face in trying to make the world a better place - ‘radical uncertainty’ is unresolvable. It’s about learning the wisdom to embrace those uncertainties, while still taking resolute action - in ways that align scientific and quantitative rationality with lived experience, emotion and intuition.

Suggested Further Reading

Toby Ord, The Precipice

Ord, MacAskill and Bykvist, Moral Uncertainty

Nate Silver, On the Edge

Eliezer Yudkowski, Rationality: From AI to Zombies

Marchau, Walker, Bloemen and Popper, Decision-Making under Deep Uncertainty

King and Kay, Radical Uncertainty

David Deutsch, The Beginning of Infinity

Daniel Kahneman, Thinking, Fast and Slow

Todd and Gigerenzer, Ecological Rationality

John Vervaeke, Awakening from the Meaning Crisis (Part 1)

Vervaeke and Riedl, ‘Rationality and Relevance Realization’

Kiverstein and Wheeler, Heidegger and Cognitive Science

Great post and summary of the progression of thinking in this space. I went through a similar analysis myself when I wrote my book "An Engineer's Search for Meaning". I concluded the book with the following recommendations:

1. Our ultimate (and automatic) goal is to perform actions that expand and enrich life and consciousness in all its forms.

2. A good way to achieve this is to periodically check and realign our actions with the SixCEED Tendencies that universe itself displays inherently (Coherence, Complexity, Continuity of Existence or Identity, Curiosity, Creativity, Consciousness, Evolution, Emergence and Diversity).

3. A good way to tune into these universal tendencies is to practice mindfulness at all times.

4. Put your highest trust in evidence and reason, but don’t turn it into dogma or zealotry because there are a lot of unknowns, uncertainties and nebulosity in reality. So one must always remain humble, willing to learn and improve.

Excellent and insightful analysis, thank you Jonah! You haven't mentioned Dave Snowden and his influential "Cynefin" approach, which to me seems to lead to something similar, but I'll leave you or others to do the comparison.

At the risk of being predictable to those who know my own tendencies, what I'd add to this (and I don't see it as taking away anything) is the collective dimension. From what I experience as well as what I read, decisions made collectively in the context of a well-functioning group tend to be of better quality than those taken by individuals alone — whatever the depth of their private analysis, reflection and meditation. And this is what I would bring into the conversation. Yes, by all means, work with your own individual "lived experience, emotion and intuition", and then bring that back to the trusted group for collective discernment. That's how Quaker concerns are supposed to work, however seldom it actually happens. And that's similar to what many people have expressed over the ages, from traditional and indigenous circle practices to several contemporary writers.

What I'm most keen on here is to bring to awareness the residual latent individualism carried over from the "modern" paradigm, and to address that, alongside the very helpful questioning you have set out above.