What is Metamodernism?

An overview and typology

‘Metamodernism’, Midjourney

As I write this in early 2025 Metamodernism is something few people have heard of. A search on Google Trends shows it to be about as popular as a search term as ‘Integral Theory’ and ‘Polycrisis’ - which few people have heard of either.

Yet the word features in the titles of a growing number of academic articles and books. A search on Amazon reveals 29 books on the topic, the vast majority of which were published in the last 5 years.

There’s a mix here of more academic works, like Jason Storm’s Metamodernism: the Future of Theory (2024) and Spencer Jordan’s Metamodernism and the Postdigital in the Contemporary Novel (2024) and those aimed at a more popular audience, like Greg Dember’s Say Hello to Metamodernism (2024) and Lene Anderson’s Metamodernity: Meaning and hope in a complex world (2019).

So, if you’re not one of the few that have heard of it yet: metamodernism is an emerging concept that is both a topic of hard-headed academic research, and thought to be of wide relevance and worthy of popularisation. Potentially interesting, right?

In this post I’ll briefly survey the terrain as it currently stands. While there are a number of other posts and webpages out there introducing metamodernism, I’ve found that they tend to focus on specific strands of thought, while leaving out others.

At present, Brendan Graham Dempsey’s book Metamodernism is perhaps the most comprehensive review. It also focuses, quite reasonably, on the commonalities between different approaches. Given the current quite disunified state of the field, I think that it’s also of value to look at differences of approach, in a kind of typology of metamodernist theories - as long as we keep in mind the overlaps and vibrant connections between the various types.

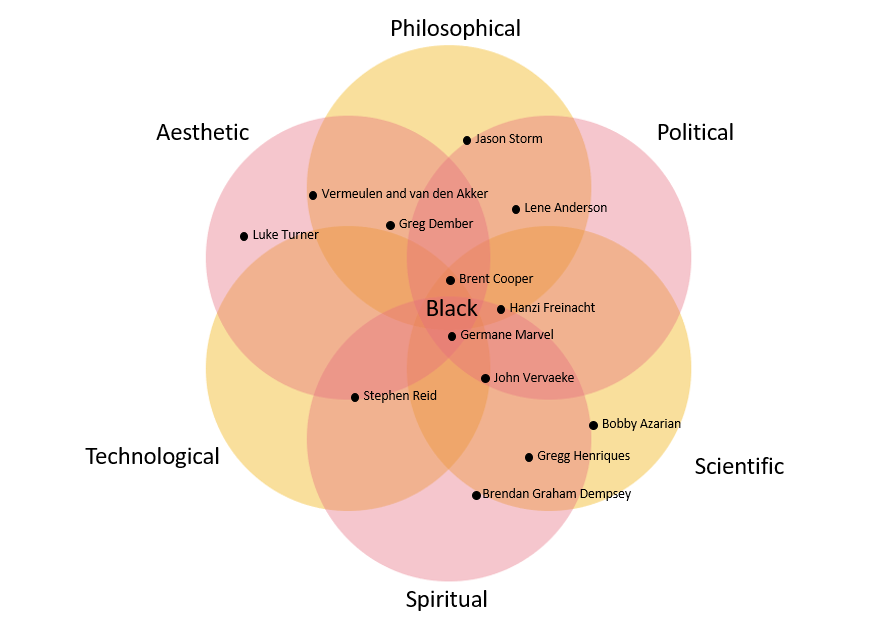

This chart may offer a useful (though inevitably inexact) way of mapping Metamodernism’s types and their overlaps.

Aesthetic Metamodernism

The term metamodernism was first introduced in literary theory and art criticism, so it makes sense to start there. As Dempsey observes, while the earliest use of the term go back to 1975 (literary theory) and 1999 (art criticism), it is a 2007 article by Alexandra Dumitrescu that most clearly anticipates current ideas: here metamodernism is framed for the first time as a “cultural paradigm” that transcends and integrates both modernism and postmodernism.

This idea of metamodernism as the emerging cultural ‘phase’ or Zeitgeist, succeeding postmodernism, became central to a small metamodern movement involving both academics and artists, and expressed in conferences, webzines (such as Vermeulen and van den Akker’s Notes on Metamodernism), and artistic productions - most prominently the performance art fronted by Hollywood actor Shia LaBeouf.

How does metamodernism transcend and include the postmodern? A key concept in Luke Turner’s Metamodernist Manifesto (which inspired Shia LaBeouf’s involvement) was that of an ‘oscillation’ between and beyond “irony and sincerity, naivety and knowingness, relativism and truth, optimism and doubt”.

As also articulated by Vermeulen and van den Akker, the poles of this oscillation can be thought of as postmodern (irony, knowingness, relativism, doubt) and modern or premodern (sincerity, naivety, truth and optimism) modes of being.

In a context of multiple global crises and the ‘return of history’, aesthetic metamodernism promotes a return of sincerity and hope to replace the cynical skepticism of postmodernist thought - but, crucially, in a way that incorporates the postmodern appreciation for the multiplicity of perspectives and modes of knowledge.

Everything Everywhere All At Once (Media Image)

The hit 2022 film Everything Everywhere All at Once offers a nice example of this. The cosmological multiverse portrayed in the film serve both as a nod to ‘modern’ scientific theories of parallel universes, and as a metaphor for a ‘postmodern’ plurality of perspectives.

And the film’s conclusion offers a hopeful response to the nihilism (represented by the Everything Bagel, for those who have seen it) that can seem to stem from this dizzying plurality. ‘Be Kind’, in the final words of one of the main characters, is a simultaneously sincere and ironic message.

Philosophical Metamodernism

While influenced by Aesthetic Metamodernism, Jason Ananda Josephson Storm’s book Metamodernism: the future of theory effectively transforms the scope of metamodernism from being a Zeitgeist or cultural phase, to something even more ambitious: a new theoretical paradigm for the humanities and social sciences.

The idea is still to ‘transcend and include’ modernism and metamodernism, but now on a philosophical rather than aesthetic plane.

The generalised scepticism and nihilism of postmodern critique is shown up as pragmatically self-undermining:

Metamodernism is what we get when we take the strategies associated with postmodernism and productively reduplicate and turn them in on themselves. This will entail disturbing the symbolic system of poststructuralism, producing a genealogy of genealogies, deconstructing deconstruction, and providing a therapy for therapeutic philosophy.

The approach that emerges is a simultaneously empirical and philosophical methodology for the social sciences, based on a recognition that ‘social kinds’ are both socially constructed and real, both permanently in flux and provisionally knowable.

Political Metamodernism

Storm’s book ends by pointing towards a politics of human flourishing that he calls ‘Revolutionary happiness’, which brings out the implicit ethical force in postmodern critiques of society. This brings us to an in some ways still more ambitious framing of metamodernism.

In a series of books offering a ‘metamodern guide to politics, Hanzi Freinacht (the pseudonym of co-authors Daniel Gortz and Emil Esper Friis) presents an unabashedly utopian political project. A metamodern society will be one that solves the basic problems of our current ‘modern’ society, including ecological sustainability, excess inequality, alienation and stress.

Freinacht draws on stage theories of psychological development to propose a future welfare system that will “spur the psychological development of larger parts of the population into the higher stages” while meeting psychological needs such as belonging, esteem and self-actualization.

What distinguishes this project from other ‘utopian’ projects is that it’s conceived as a ‘relative utopia’. It steers between the ‘modern’ fallacy of a final end-goal for society, and the ‘postmodern’ fallacy that utopian thinking is fundamentally flawed, by acknowledging that solutions to social problems always bring new, hard-to-anticipate problems in their wake - while still being genuine solutions to the original problems.

With this characteristically metamodern move Freinacht recognises the truth in claims (by e.g. Steven Pinker and others) that the modern European Enlightenment has solved major problems of earlier societies, while also recognising the truth in critiques of Enlightenment by postmodern and critical theory.

Technological Metamodernism

For many today, politics is inseparable from the governance of technology, from social media platforms that threaten the underpinnings of deliberative democracy, to developments in AI that herald social disruption and on some views the potential end of humanity.

Technological metamodernism can be seen as the variant of political metamodernism that corresponds to this point of view. Stephen Reid’s open-sourced course with that name is among the best resources in this area (at least until his book on the topic is finished).

The course, which includes Emil Esper Friis (Hanzi Freinacht) and others as guest speakers, connects metamodernism directly with the literature around AI risk, including ideas from the ‘rationalist’ community and the influential online forum LessWrong.

A key idea is that of transcending the debate between (postmodern) technoskeptics like Cathy O’Neil and Jaron Lanier on the one hand, and a (modern) rationalist camp composed of both AI ‘doomers’ like Eliezer Yudkowski and the effective accelerationism of Guillaume Verdon (known as ‘e/acc’ on social media) on the other.

Technological metamodernism on this view seeks to unlock the genuine promise of technology via an ‘axiological design’ that incorporates values into software engineering, both in terms of the user experience and by identifying unexpected harms or externalities via ‘yellow teaming’.

It also considers the ways in which mythic and spiritual experience can be reinterpreted in a scientific and technological context, in a way that includes headsets for lucid dreaming, the neuroscience of psychedelics and meditation, and a renewed role for myth and imagination.

Spiritual Metamodernism

It might seem that this turn to the spiritual puts us some distance from the kinds of metamodernism we discussed at the outset. But such a turn is arguably a pervasive theme of the movement.

Vermeulen and van den Akker point out that the new ‘depthiness’ they associate with aesthetic metamodernism can be thought of as a neo-romantic turn, in the spirit of romanticism’s deeply spiritual efforts to “turn the finite into the infinite, while recognising that it can never be realised”.

Although not central to his philosophical metamodernism, Storm sees “various contemplative practices as important to Revolutionary happiness” (having previously written a book on the role of magical and esoteric traditions in the development of the modern human sciences).

Similarly the theory of psychological development behind Freinacht’s political metamodernism has a significant place for spiritual experiences, though they are sharply distinguished as ‘states’ from the ‘stages’ of cognitive and cultural complexity that more strongly define their political project.

It is probably Brendan Graham Dempsey who has most effectively put spirituality at the heart of the metamodernist project. From his early contributions to the Notes on Metamodernism webzine, to his books Metamodernism and the return of Transcendence (2021) and Emergentism: A religion of complexity for the Metamodern Age (2022), Dempsey articulates a specific vision of metamodern spirituality, while bringing together like-minded thinkers through a podcast and other initiatives.

‘The universe is waking up’, Midjourney

Dempsey’s vision is, again as in romanticism, of a transcendent dimension immanent in the natural world. Unlike the romantics, however, Dempsey draws on natural science in articulating how human cognition, including spiritual experience, is continuous with and emerges out of the physical world.

Scientific Metamodernism

This brings us to scientific metamodernism, which we can think of as the set of scientific paradigms that ground the metamodern worldview, including its spiritual dimension.

A key thinker here is Bobby Azarian, whose Romance of Reality was published to critical acclaim in 2022. Azarian draws together various recent strands of work in complexity science, biology, neuroscience and cosmology to weave a grand narrative of the evolution of matter, life, intelligence and consciousness.

Complexity science - the science of emergent patterns of behaviour in complex systems made up of very large numbers of parts, and pioneered by the Santa Fe Institute since the 1980s - is a unifying explanatory tool here, since it applies across multiple disciplines and domains to explain the recurrent emergence of hierarchical levels of agency in a physical universe.

The metamodern aspect of this ‘paradigm of emergence’ can be seen in the fact that it combines the rigorous mechanistic and mathematical methods of modern science with a critique of reductionism - since an emergent property is precisely one whose behaviour cannot be ‘reduced’ to the level from which it emerges.

Because the emergence of life and intelligence is understood as a natural process that occurs with high likelihood under specific physical conditions, it becomes possible to speak in a new way of a cosmic teleology, or directionality within evolution. This allows a renewed, scientifically-based sense of meaning, or of being ‘at home in the universe’ (to quote the title of a book by complexity theorist Stuart Kauffman).

Cat's Eye Nebula (NGC 6543), Hubble Space Telescope, 2008

This is not simply a return to a premodern sensibility, however. To the extent that this viewpoint supports a new religiosity, it’s a “religion that’s not a religion”, in the phrase used by John Vervaeke - whose use of cutting-edge cognitive science to engage with questions of meaning and spirituality can be seen as another example of scientific metamodernism.

A scientific ‘meta-religion’ as Dempsey describes it, instead offers “a path for the cultivation of transcendence and transformation not based in supernaturalism and authority, but reflective rationality and supportive pedagogy”.

Black Metamodernism

Black metamodernism offers a way of reframing many of the themes in the previous sections. As an alternative tradition sometimes overlooked relative to the ‘Dutch metamodernism’ of Vermeulen and van den Akker, and the ‘Nordic Metamodernism’ of Lene Anderson and Hanzi Freinacht, it can be traced back to art historian Moyo Okediji, who used the term metamodernism in 1999 to refer to a “challenge to modernism and postmodernism” when discussing the interconnections between African and African-American art.

In recent years, Germane Marvel has developed black metamodernism as “an emerging approach to clarifying, enriching and grounding the metamodern project”.

Philosophically, Marvel draws on Vernon J Dixon’s concept of ‘diunital thinking’, which includes the ability to embody ‘both/and’ logic in a new kind of emotional intelligence: one that encompasses cognitive dissonance and multiple perspectives.

Politically, as Brent Cooper has written, Black metamodernism cannot be reduced to ‘postmodern’ identity politics, but references Martin Luther King in transcending and including the racial struggle in a “larger quest for socio-economic and even environmental justice…to address the meta-crisis of hyper-capitalism”.

Relatedly, Black metamodernism seeks to challenge “the supremacy of lightness” that manifests both in unwarranted Eurocentrism, and in spiritual approaches that seek what is sometimes described as the pure ‘light’ of consciousness, while bypassing “the body, nature, feelings and relationships”.

Thanks for laying all this out in a succinct and readable way.

"Given the current quite disunified state of the field..."

I would suggest considering that what you're looking at is not a single yet disunified field, but rather a set of various different fields with little in common, all claiming the same term as the name for their field. I can tell you at least, as an author within what you've called "aesthetic metamodernism," that our large network of authors and researchers do not largely see connections with the other areas that you've discussed in this article (with the exception of Jason Storm's work which does seem to have some important degree of meaningful overlap -- I wrote about this in my own book).

I appreciate that you attempted to map out the differences, but even in doing so, I feel you assumed more connection than there even is.