Metacrisis: an Overview

Key perspectives to date, and some open questions

‘Metacrisis’ has emerged in recent years as a new concept for understanding 21st century global challenges.

Probably its most well-known proponent is Daniel Schmachtenberger, who has helped the concept find a large audience with highly articulate video interviews attracting hundreds of thousands of views.

On his way of presenting it, the concept refers to the existence of structural root causes or ‘generator functions’ of the many catastrophic and existential risks that humanity currently faces - such as ecological destruction, threats from AI, or nuclear war.

These generator functions include perverse economic incentives and so-called ‘multipolar traps’ - system dynamics in which individuals acting in seemingly rational ways end up collectively trapped in situations that none of them individually choose. No one wants climate change, for example, yet the global system evolves towards this outcome due to structural factors, such as disincentives for individual nations to decarbonise at scale.

While this framing may be the most widely known, there’s a wide range of other perspectives in recent metacrisis discussions - and this has led to confusion about what is meant by the term.

In what follows I’ll explore the territory, tracing the history of the term’s adoption, and mapping boundaries and some open questions.

I’ll suggest that recent metacrisis framings fall into two main kinds, depending on whether they emphasise ‘inner’ psychological or cultural factors or ‘outer’ economic or structural dynamics. (I’ll also consider ways in which these two approaches complement each other, rather than being in conflict.)

I’ll end by clarifying the significant areas of coherence in recent discussion, while also highlighting areas of disagreement and key questions for further research.

Early Usage: Limits to Growth and Technological Innovation

The influential Club of Rome came close to coining the current term over 50 years ago. One of its founding documents in 1970 set out the idea of a “world problematique” or “meta‐system of problems” which need to be addressed in an integrated way:

The fragmentation of reality into closed and wellbounded problems creates a new problem whose solution is clearly beyond the scope of the concepts we customarily employ. It is this generalized meta-problem (or meta-system of problems) which we have called and shall continue to call the "problematique" that inheres in our situation.

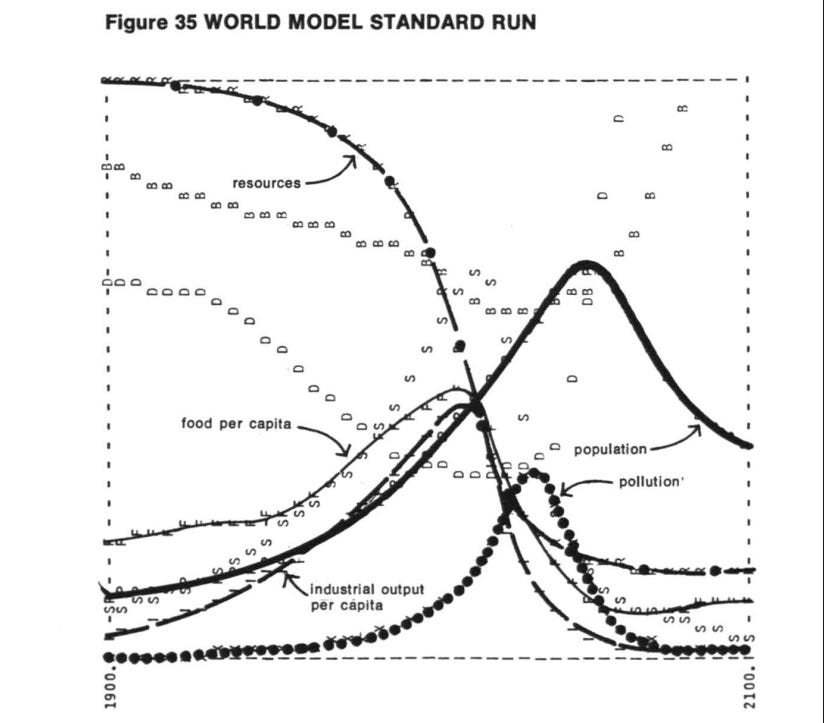

This report was followed by the more widely known 1972 report on The Limits to Growth, which, similar to Schmachtenberger, identified specific system dynamics - namely exponential population growth and resource consumption - as root causes of threats to human civilization. (While the World3 computer model that formed the basis for the report has serious limitations, it’s been argued that data from more recent decades continue to conform to the model.)

As regards the specific term ‘metacrisis’ however, a search of academic databases shows only a few instances before 2010, and these tend to a narrow usage that falls short of global civilizational crisis – for example, an article that uses the term to describe Middle Eastern political stalemates.

A 2011 paper by economists David J. Lane and Dimitri van der Leeuw appears to be the first time the term “metacrisis” is used in the more wide ranging sense adopted by Schmachtenberger. Entitled ‘Innovation, Sustainability and ICT’ it argues that

Our society is increasingly beset by what it interprets as global crises, of which the financial crisis, the energy crisis, and the global warming crisis are leading examples. We argue that all these crises share a common origin in what may be described as a social meta-crisis, induced by the way in which our society organizes its processes of innovation.

The focus on technological innovation policy as a root cause of global crises anticipates Schmachtenberger’s concern that perverse incentives around innovation - particularly in the field of AI - are among the generator functions of existential risk.

Schmachtenberger points out that in a competitive market economy, AI companies have financial incentives to seek first-mover advantage at the expense of good governance around safety and social impact.

Lane and van der Leeuw suggest that such incentives need to be considered in the context of what they call the “Innovation Society ideology” which sees economic growth driven by innovation as a primary goal of government policy and business strategy.

Foundations: Metatheory and Theology

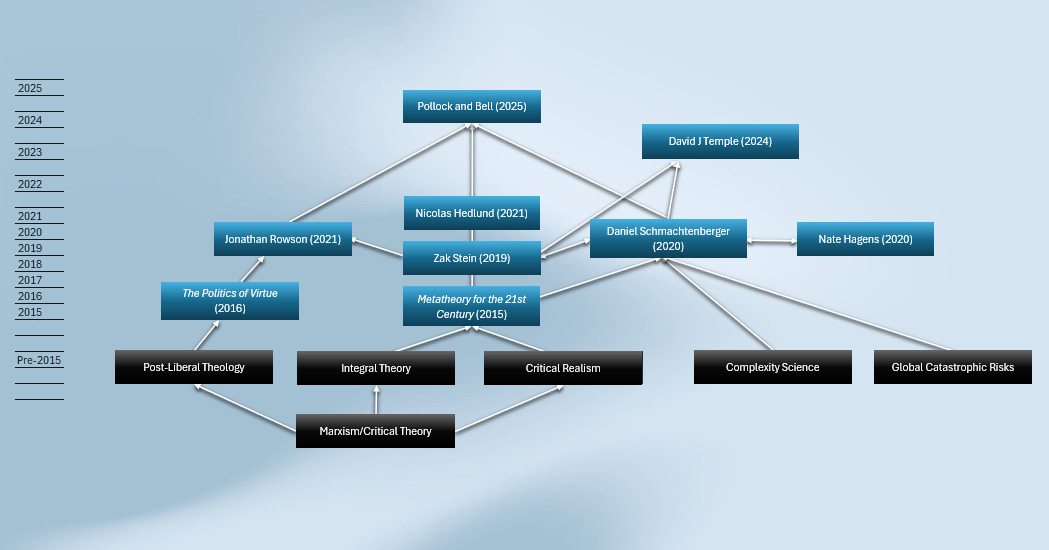

Around 2015 we find two developments of the use of the term that achieve a wider resonance. Strikingly, these appear to occur independently of each other - at the same time within two different intellectual traditions - suggesting a logical convergence of ideas.

Integrative Metatheory and Critical Realism

Beginning in the early 2010s, a series of conferences were organised bringing together Ken Wilber’s integral theory and Roy Bhaskar’s critical realism. The term ‘metacrisis’ as a descriptor of multiple global challenges with a root cause emerged in this context, appearing in print in a 2015 anthology titled Metatheory for the 21st Century: Critical Realism and Integral Theory in Dialogue.

In the introduction to the volume, authored by Mervyn Hartwig, Nicholas Hedlund, Roy Bhaskar and Sean Esbjörn-Hargens, the idea of metacrisis is set out in comparison to related ideas of ‘hypercomplexity’, ‘wicked problems’ and ‘polycrisis’:

Our own preferred term for this complex multiplicity is ‘metacrisis’. This is in part because for us it is not just a polycrisis in the sense that it is multifaceted or there are many interconnected objective or ‘exterior’ crises or wicked problems occurring (e.g., political, economic, and ecological). These interconnected crises are also situated in a(n) (inter)subjective context of ‘interior’ meaning making (semiosis), construal and response that includes philosophical, scientific, religious, existential, worldview, and psychospiritual dimensions that are essential to include in an adequate understanding of the complex dynamics in play in order to facilitate more effective responses.

This concept of metacrisis is rather different from Schmachtenberger’s. Both approaches seek to understand multiple global crises in an integrated way. But while Schmachtenberger emphasises structural causes such as perverse incentives, this ‘metatheory’ approach emphasises the need to supplement ‘external’ structural analysis with a focus on ‘internal’ cultural and psychological factors.

And it’s notable that the term ‘metacrisis’ emerged here in the context of research communities in which the ‘meta-‘ prefix was already being used to describe an overall theoretical approach: metatheory.

Both Critical Realism and Integral theory were methodologically committed to multi-dimensional analysis - as in Wilber’s AQAL (all quadrants all levels) approach and Bhaskar’s idea of a ‘laminated system’. The concept of metacrisis is a natural consequence of applying a multi-dimensional approach of this kind, to planetary crises.

Metacrisis and metatheory are inter-related, on this view. Metatheory emerges as critically important, both in addressing the multi-dimensional nature of the metacrisis, and in identifying it as such in the first place - since more narrow approaches to specific global crises such as ecological catastrophe or AI risk tend to obscure the wider metacrisis perspective.

Post-liberal Theology

At almost exactly the same time, the term metacrisis also appeared in print in a very different intellectual milieu: that of post-liberal academic theology.

In 2016 theologian John Milbank and political theorist Adrian Pabst published The Politics of Virtue: Post-Liberalism and the Human Future. They argued that Western modernity is undergoing a fundamental crisis – a “meta-crisis of liberalism.”

Drawing on a tradition of Christian social thought blended with Marxian critique, they trace social, economic, and environmental crises to what they see as the failings of the liberal worldview: radical individualism, loss of community, and spiritual void:

Just as liberal thought has redefined human nature as fundamentally individual existence abstracted from social embeddedness, so too liberal practice has replaced the quest for reciprocal recognition and mutual flourishing with the pursuit of wealth, power and pleasure – leading to economic instability, social disorder and ecological devastation.

Their solution calls for a return to older ideas of virtue, community, and even religiosity - essentially a cultural and ethical renewal to heal the crisis.

This is a perspective that resonates strongly with some recent non-academic discussions - like the dialogue between John Vervaeke, Iain McGilchrist, and Daniel Schmachtenberger on ‘the psychological drivers of the metacrisis’ which attracted over 400,000 views on Youtube, and which covered the need for new forms of spirituality to address the metacrisis.

Pabst and Milbank’s work, however, is not usually seen as a source for such views. Overall, one might say that while it has been well-received in academic and theological circles, including a positive review by former Archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams, it is the Metatheory approach that has had more of an impact on the para-academic world of podcasts, blogs and Youtube discussions, as well as books aimed at a wider audience.

Zak Stein: the Education Metacrisis

An example of the latter is the influential work of Zak Stein. While doing doctoral work at the Harvard University on the philosophy of education, Stein also participated in the Metatheory conferences in the early 2010s, contributing a chapter to the volume already discussed.

Soon afterwards Stein developed these ideas into a book entitled Education in a Time between Worlds (2018), in which he argues for “the central importance of education as an aspect of the global meta-crisis”.

Education here does not mean simply schooling, but rather the way in which culture is transmitted and developed between generations. And Stein points to the way in which computer technologies have the potential to revolutionise educational practice for children and adults alike, resulting in both risks and opportunities at a civilizational scale.

A 2022 article Education is the Metacrisis sharpens the focus on the metacrisis, which he defines as a whole composed of four interwoven sub-crises - of meaning, sense-making, capability and legitimacy - all of which relate to the intergenerational transmission of culture, and are best addressed from the perspective of an integral educational practice.

Welcome to the metacrisis. This is a generalised educational crisis in which, despite all the concrete problems faced by society, the most pressing problems are actually “in our heads” (i.e., in our minds and souls, we are in a crisis of the psyche).

While adding a useful and innovative framing in terms of a broad notion of education, this conception of metacrisis is clearly within the metatheory tradition that highlights the role of ‘inner’ factors alongside the more well-known ‘external’ crises of AI risks, climate change and the like.

Daniel Schmachtenberger: Metacrisis and Moloch

Zak Stein’s work also helps contextualise the ideas of Daniel Schmachtenberger that were briefly outlined earlier.

Stein and Schmachtenberger worked closely together in the period under discussion, co-founding both the Civilization Research Institute and the Consilience Project, whose websites contain much of Schmachtenberger’s written outputs to date. And although not a participant in the Metatheory conferences, Schmachtenberger has a longstanding interest in Integral theory. This connection to the metatheory tradition explains his adoption of the term metacrisis to articulate his perspective on civilizational risks.

However his emphasis on structural ‘generator functions’ can be seen as an innovative reframing of the concept, shifting the focus towards more objective, ‘external’ structures of the market economy. While the metatheory tradition was increasingly placing the inner dimension at the heart of the metacrisis - as in Zak Stein’s educational framing - Schmachtenberger suggested that despite its importance, the inner dimension itself needed to be placed in the context of perverse incentives and multipolar traps.

Introducing an important game-theoretic perspective, he argued that transformations of cultural or educational practices by themselves risk being irrelevant if they fail to address basic coordination problems.

For example, an AI company embracing a new culture of wisdom and good safety governance would likely be outcompeted by a company fuelled by an ideology of fast innovation, as the latter gained greater market share through first-mover advantage.

This perspective was likely shaped by a 2014 article ‘Meditations on Moloch’ by Scott Alexander, the author of the Slate Star Codex blog that became influential in ‘rationalist’ communities - indeed Schmachtenberger references the concept of Moloch in one of his earliest Youtube videos in 2020.

Riffing on Allen Ginsberg’s famous poem by that name, Alexander essentially defines Moloch as the god of multipolar traps (this term, adopted by Schmachtenberger, was popularised by Alexander), defined as follows:

In some competition optimizing for X, the opportunity arises to throw some other value under the bus for improved X. Those who take it prosper. Those who don’t take it die out. Eventually, everyone’s relative status is about the same as before, but everyone’s absolute status is worse than before. The process continues until all other values that can be traded off have been – in other words, until human ingenuity cannot possibly figure out a way to make things any worse.

While the idea of multipolar traps is closely related to concepts such as ‘coordination failure’ well-known to economists, what was new in the Moloch framing was seeing such failures through an evolutionary and world-historical lens, and thereby revealing their centrality for key civilizational risks.

Like Schmachtenberger, Alexander points to the analogies between existential risk from AI, understood as the threat of a superintelligent system destroying humanity by optimizing for narrow goals, and wider societal and evolutionary systems of game-theoretic incentives that also result in a race to the bottom, where all other values are thrown “under the bus”.

Schmachtenberger’s perspective can therefore be seen as a synthesis of the concept of metacrisis found in integral metatheory with the applications of game theory (Moloch) and concepts of existential risk (especially from AI) found in the rationalist community.

But he also goes beyond both these sources, in the way he draws on complexity science to develop a notion of evolutionary ‘attractors’ within world-historical systems. A civilization that integrates both ‘inner’ wisdom and ‘external’ coordination capacity at planetary scale could be, he proposes, a “third attractor” beyond unsustainable market-based systems and authoritarian dystopias.

Nate Hagens: Biophysical Metacrisis

Another metacrisis perspective that extends and complements Schmachtenberger’s is that of Nate Hagens.

Hagens, who left a finance career on Wall Street to focus on research in this area, is perhaps best known as the host of The Great Simplification podcast, but has also authored a peer-reviewed article in 2019 and two books (co-authored with DJ White, the co-founder of Greenpeace). His 8-part series of Youtube discussions with Daniel Schmachtenberger from 2022-2024 provides insights into how his approach complements Schachtenberger’s.

While Hagens is not especially attached to the term ‘metacrisis’ (which does not feature in the 2019 article in which he outlines his key ideas) he does use it to refer to the clash between the fossil-fuel powered modern economy and thermodynamic planetary limits.

Standard economic perspectives, he thinks, are ‘energy-blind’ in the sense that they fail to appreciate the critical role of energy-rich fossil fuels as driving modernity’s economic growth. The temporary energy windfall provided by this ‘carbon pulse’ pumped unprecedented surplus into human societies, enabling population growth, technological complexity and ever‑faster economic throughput. It also locked those societies into a metabolism that cannot be maintained as net‑energy returns decline and extraction becomes costlier.

As Hagens puts it, the global economy behaves like an “Economic Superorganism.” Its emergent goal is power maximisation: convert as much energy as possible into goods, services and status in the shortest time. That imperative makes the system both dynamic and brittle - for example, the financial super‑structure of debts and expectations is now far larger than the biophysical foundation that ultimately has to redeem it.

Like Schmachtenberger, this biophysical conception of metacrisis focuses on objective system dynamics: in this case those defined by physical facts about human energy consumption and limited fossil fuel stocks.

But Hagens also connects these dynamics to inner dimensions, namely the evolutionary psychology of brains that evolved for short‑term status competition, and immediate reward on the savannah. These ancient instincts, once adaptive, are now a key part of the problem - which points to the need for a cultural evolution that transcends these longstanding patterns.

Jonathan Rowson: Epistemic Metacrisis

While Hagens and Schmachtenberger have continued to develop their more ‘external’ framing of metacrisis over the last few years, others have developed the more ‘internal’ focus found in the Metatheory tradition and Zak Stein’s work.

A distinctive and influential approach in this vein is provided by Jonathan Rowson, chess grandmaster turned co-founder of metamodern praxis community Perspectiva, in his 2021 essay Tasting the Pickle.

Describing himself as a recovering ‘cartographical hedonist’, the essay suggests multiple ways of mapping the metacrisis, including “four main patterns, unpacked as ten illustrations”. I won’t try to outline all of these, though I’ll note that the four main patterns - socio-emotional, epistemic, educational and spiritual - all tend to the inner side of the inner/outer dichotomy. Moreover the ‘educational’ element here explicitly draws on Zak Stein’s work - and indeed Stein is a co-contributor to the volume Dispatches from a Time Between Worlds: Crisis and Emergence in Metamodernity, edited by Rowson.

But Rowson also engages explicitly with Schmachtenberger’s ideas, suggesting that the focus on inner dimensions should not be thought of as an alternative to framing the metacrisis in terms of objective generator functions, but a way of addressing precisely the collective action problems that framing identifies.

Referencing Elinor Ostrom’s well-known empirical work on how real communities solve collective action problems, Rowson points to the way in which such problems have socio-emotional, epistemic, educational and spiritual roots.

Drawing on comments made by Schmachtenberger himself, that stewarding godlike technologies requires the wisdom of Bodhisattvas, Rowson takes this idea seriously as a call for an educational praxis that cultivates receptivity to ways of life that are more open to “trans rational phenomena” - and here Rowson explicitly references mythopoetic experience of the sort found in William Blake’s prophetic works.

This spiritual or religious dimension here echoes the theological roots of The Politics of Virtue, which he also refers to, and there is a sense in which Rowson offers a synthesis of all the previous metacrisis framings we’ve discussed.

But I suggest that what’s most distinctive about Rowson’s perspective is actually its focus on perspectivity as such. It’s the epistemic dimension of the metacrisis, the apparent impossibility of conceptually mapping the territory because, as he puts it, “the territory is full of maps”, that explains both the more personal, meandering style of the essay, and its title.

‘Tasting the pickle’ refers to the importance given to grasping the metacrisis at a level more sensual and aesthetic (the word ‘taste’ referring to both these dimensions) than a purely conceptual mapping allows.

In one way this can be seen as practical supplement to the previous more purely theoretical approaches to the metacrisis, a vital emphasis on the importance of embodying one’s conceptual understanding and of seeing - in the intuitive way Rowson has learnt from his years as a chess champion - the right way to respond in the specificity of one’s personal context.

But seen from another angle, Rowson’s epistemological metacrisis undermines those other approaches: a territory full of maps - riven by fundamental epistemological and ontological disagreements - may be simply too complex for metatheory to gain a foothold.

It is also a place where we need to be sceptical of theory-driven optimism, for example expecting too much from the concept of ‘emergence’ or that “widespread integral consciousness will forge within everyone’s hearts and minds any time soon”. On the contrary, Rowson claims to agree with American author Meg Wheatley when she claims that “we simply cannot effect systems change at scale in the way we keep saying we have to”.

The epistemic difficulties in mapping the metacrisis make it all the harder to plot a way out using theory alone. But this does not stop us from feeling our way to an embodied - even spiritual - perception that can guide us to practical action, and a kind of social hope amid our conceptual confusions.

Synthetic Approaches: Hedlund and Smith

I’ve suggested that metacrisis theories fall into two main camps, based on whether they focus on ‘inner’ or ‘outer’ root causes of global crises. But it’s natural to wonder whether these two approaches are complementary, rather than being alternatives: could it not be that there are both ‘inner’ and ‘outer’ root causes at work?

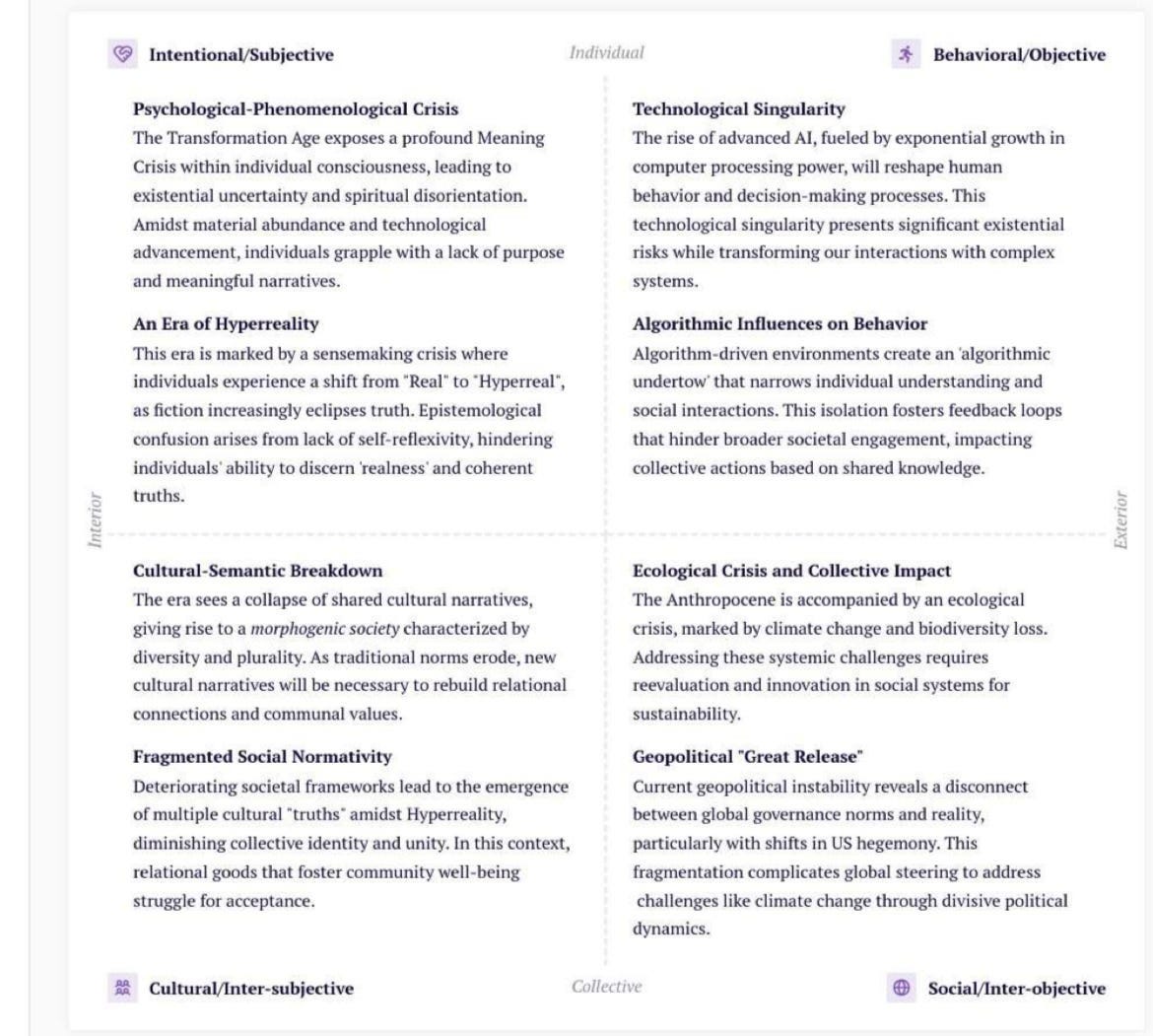

Indeed this idea resonates with the original ‘Metatheory’ approach. A multi-layered approach such as the ‘All Quadrants All Levels’ perspective of Integral theory will tend to identify a combination of inner and outer crises and causes in the left and right quadrants of Ken Wilber’s well-known schematic.

This kind of perspective has been explicitly put forward by Integral theorist Robb Smith in recent papers. His paper ‘A Sociology of Big Pictures’, for instance includes the following chart:

Similarly, Nicolas Hedlund, who together with Sean Esbjörn-Hargens introduced the term metacrisis in the Metatheory volume discussed earlier, has continued to develop the ideas expressed there in a PhD thesis at University College London, proposing a ‘pandimensional’ view he calls ‘Visionary realism’:

According to the visionary realism’s pandimensional realism, the underlying generative mechanisms or causal roots of the metacrisis exist, and actualize symptom-events, in all dimensions of social reality—in the interior-individual (psychological); interior-collective (cultural); exterior-individual (biological); and exterior-collective (socio-ecological) dimensions (p284)

The question raised by these synthetic approaches, however, is whether they collapse the distinction between Metacrisis and Polycrisis - a distinction that is critical in justifying the introduction of the newer term in the first place. This is because the pandimensionalist or ‘four-quadrant’ metacrisis described by Hedlund and Smith would seem to fit a standard definition of polycrisis as a system of multiple, inter-related crises that needs to be treated holistically.

Hedlund confronts this concern in his thesis, arguing that it is the inclusion of ‘inner’ factors within the with pandimensional lattice that distinguishes metacrisis from polycrisis:

A factor that distinguishes the metacrisis from the poly-crisis and other similar notions of our predicament is that, while the latter highlights that there are many different crises occurring simultaneously and recognizes that many of these are interconnected, the former goes a step further to draw on insights and distinctions from visionary realism to reveal the epistemological and ontological, semiotic as well as material, interior as well as exterior, meta-systemic dynamics at play.

In fact, he goes on to suggest that the epistemological dimension may have a kind of primacy, tipping us back to the ‘inner’ side of the spectrum. Specifically, he suggests that an epistemological notion of ‘alethic resonance’ - a metamodern concept that navigates between modern conceptions of objective reality and postmodern relativism - may be the key to responding to metacrisis.

It’s worth noting that, by comparison to the sceptical vein in Rowson’s framing of the ‘epistemological crisis’, this is a move towards an optimistic epistemology.

Other recent approaches: David J Temple, and Pollock and Bell

Other recent approaches operating within a broadly Integral tradition are likewise optimistic about the ability to diagnose specific root causes at the ‘inner’ end of the spectrum.

In a book titled First Principles and First Values: Forty-Two Propositions on CosmoErotic Humanism, the Meta-Crisis, and the World to Come, Mark Gafni, Zak Stein and Ken Wilber, writing under the joint pseudonym David J Temple, propose that the underlying root cause is in fact a ‘global intimacy disorder’.

Intimacy is here understood as not just an interpersonal concept, but an attitude that can also hold between human beings and the natural world in a ‘cosmoerotic humanism’.

The ‘generator functions’ of zero-sum rivalry are explicitly mentioned - and indeed Schmachtenberger is described as a collaborator in the Center for World Philosophy and Religion, the institution within which the book was written. But the argument is that such game-theoretical dynamics depend on a cultural intimacy disorder in which both human beings and nature itself are treated instrumentally, rather than as participants in a field of shared value.

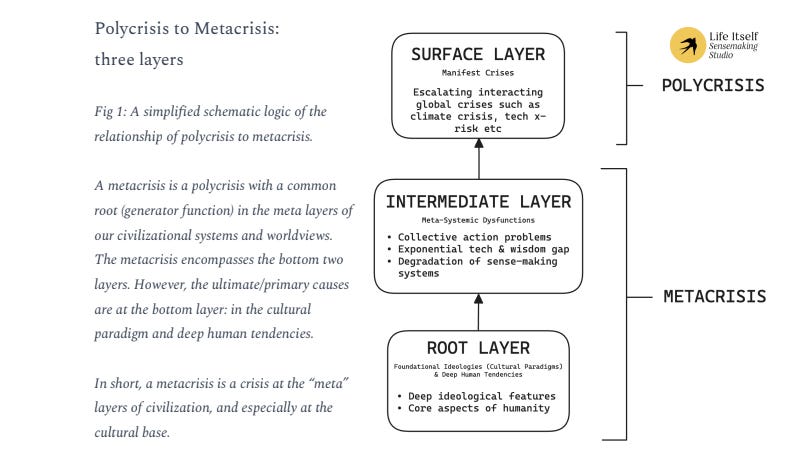

Likewise, a recent white paper From Polycrisis to Metacrisis co-authored by Rufus Pollock and Rosie Bell, argues that paradigmatic ideological and cultural features are more fundamental than the collective action problems discussed by Schmachtenberger, and that identifying ‘inner’ root causes is crucial in distinguishing metacrisis from polycrisis.

Pollock and Bell link these inner ideological features to the sociological and historical concept of modernity, identifying narratives of human separateness from nature, rational individualism and faith in material progress as roots of both climate crisis and runaway AI.

Like Rowson, they identify epistemological challenges in the fact that people “rooted in the modern paradigm” will require a major shift in worldview to even become aware of the metacrisis. But they are more optimistic that such shifts are both epistemologically justified and practically possible - whether through “meditation practice that dismantles the self view and the story of separateness” or more theoretical work.

Open Questions

This overview of key metacrisis perspectives has hopefully made clear that there’s significant coherence and agreement in the way the term has been used.

There is general agreement that metacrisis is distinct from polycrisis, and that this distinction lies in part in the fact that there are psychological or cultural dimensions of the crisis, that need to be targeted alongside structural or economic dimensions.

There is general agreement that there are no easy answers, and that any solution will need to be holistic in nature - rather than targeting specific crises, such as environmental destruction, or existential AI risks, in isolation.

At the same time, there are areas of disagreement which constitute key open questions for ongoing discussion.

First of all, there’s the question implicit in my classification of two kinds of metacrisis views: are inner factors in some sense more fundamental than outer ones? Although as we’ve seen a number of recent voices have said that they are, I read Schmachtenberger in particular as making a strong case that collective action problems and related rivalrous system dynamics need to be foregrounded in both theoretical diagnoses and pragmatic responses.

This dialectic is clear in the recent three-way debate between Schmachtenberger, Vervaeke and McGilchrist. While his interlocutors agree on the centrality of psychological factors, Schmachtenberger questions (despite agreeing that such factors are important) the extent to which a pragmatic focus on reimagining education for the cultivation of wisdom, community and brain-hemispheric balance can be effective at scale, in a context where game-theoretic dynamics resist the desired outcomes.

So a key open question is whether these Molochian dynamics, despite their psychological and cultural roots, nevertheless have an emergent independence that needs to be independently and directly addressed in responding to metacrisis.

Another key question is about the structure of the metacrisis. There are a number of recent attempts to describe the structure of polycrisis in a rigorous way using the tools of complexity science, including some recent work in the Cambridge journal Global Sustainability.

As we saw when considering Hedlund’s synthetic approach, one way of thinking about metacrisis is that it shares the same systemic structure as polycrisis, but includes psychological or cultural dimensions within that structure. This way of thinking is in the systems-theoretic tradition of the Club of Rome - and indeed a recent report to that club by Jamie Bristow and others outlines such a view (though the word ‘metacrisis’ is not used).

On the other hand one may feel that the metacrisis calls for a different mode of analysis, which brings out more clearly the idea of ‘generator functions’ or ‘root causes’ - whether conceived of as inner or outer in nature. In this vein, the term polycrisis has been criticised by Marxist thinkers, for instance, for failing to give sufficient weight to the role of capitalist structures in generating crises.

Some other questions I’d suggest remain open to further research and discussion include:

The nature and history of the psychological or cultural factors that determine the metacrisis. Are they more fundamentally shaped by our evolutionary inheritance (Hagens) or by modernity (Pollock and Bell)? Are they best described as a meaning crisis, an intimacy disorder, or something else?

To what extent is it possible to overcome the epistemic challenges presented most forcefully by Rowson, and gain objective (meta-)theoretical knowledge of the metacrisis?

In what ways can an accurate theoretical diagnosis of the structure of the metacrisis guide practical action to address it, and what precise forms might such action take?

Metacrisis Perspective Lineages

Sources Mentioned

Arnscheidt CW, Beard SJ, Hobson T, et al. (2025) ‘Systemic contributions to global catastrophic risk’ Global Sustainability

Alexander, S. (2014) ‘Meditations on Moloch’

Bhaskar, R., Esbjörn-Hargens, S., Hedlund, N., Hartwig, M., (2015) Metatheory for the Twenty-First Century

Bristow, J. Bell, R. et al. (2024). The System Within: addressing the inner dimensions of sustainability and systems change. The Club of Rome. Earth4All: deep-dive paper 17.

The Club of Rome, (1970) The Predicament of Mankind

Hagens, N. (2020) Economics for the future – Beyond the superorganism

Hedlund, N. (2021) Visionary Realism and the Emergence of a Eudaimonistic Society (PhD Thesis)

Lane, van der Leeuw et al, (2011) Innovation, Sustainability and ICT

Lawrence, M., Homer-Dixon, T., et al (2024) 'Global polycrisis: The causal mechanisms of crisis entanglement', Global Sustainability

Millbank and Pabst, (2016) The Politics of Virtue

Pollock, R. and Bell, R. (2025) From Polycrisis to Metacrisis

Rowson, J. (Ed) (2021) Dispatches from a Time Between Worlds: Crisis and Emergence in Metamodernity.

Schmachtenberger, D. (2020) ‘Converting Moloch from Sith to Jedi’, YouTube.

Schmachtenberger, D. (2023) 'An Introduction to the Metacrisis', YouTube.

Smith, R (2025) ‘Sociology of Big Pictures’

Stein, Z. (2019) Education in a Time Between Worlds

Stein, Z. (2022) ‘Education is the Metacrisis’

Temple, David J. (2024) First Principles and First Values: Forty-Two Propositions on CosmoErotic Humanism, the Meta-Crisis, and the World to Come

Vervaeke, J., McGilchrist, I., and Schmachtenberger, D. (2023) 'The Psychological Drivers of the Metacrisis'. YouTube.

Other Relevant Sources for Further Reading

Björkman, T. (2019). The world we create: From god to market.

Joshua Williams, (2023) Introduction to the Metacrisis.

Jeremy Johnson, (2023) We’re already living in a new time

Jordan hall, (2023) The Meta-Crises and Digital Identity

Johannes Niederhauser (2020) The Meta Crisis of the Meta Crisis, Youtube.

This is a really impressive and helpful piece Jonah. Great work synthesising all of this background into something approachable and seemingly robust. It will v much help my ongoing exploration of ideas and people in this area, and I am sure will help others too. Thanks for taking the time to write it and share.

Great work bringing it all together!